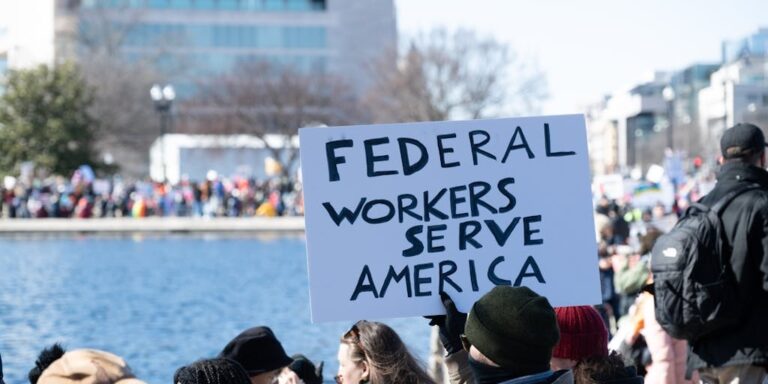

When sweeping announcements were made earlier this year that a swath of federal workers were slated to lose their jobs in the nation’s capital, neighboring state and city governments — Virginia, Maryland and Washington, D.C. — began to make the best out of a tough situation.

Perhaps, state and local leaders thought, newly unemployed civil servants might be interested in shifting their professional energy away from processing Social Security benefits and deploying foreign aid and toward teaching students in the classroom.

Recruiting websites were launched specifically focused on federal workers and their skill sets. Job fairs were scheduled. And programs for alternative credentialing for teachers, while existing long before the mass federal layoffs, ramped up.

The potential to attract new educators seemed high. Earlier this month, the U.S. Department of Labor reported that the federal government slashed 69,000 jobs since January, not including employees on paid leave or receiving severance.

Despite the doubled-down efforts, by mid-summer, state officials were unable to say whether or not it has yet made a difference in finding new instructors for schools.

“I will be transparent that it is difficult to track success unless it’s self-reported,” says Kelly Meadows, assistant state superintendent in Maryland’s State Department of Education’s division of educator effectiveness.

Similarly, Virginia did not have any educator-specific numbers to share, but said its Virginia Works program recently connected 15,000 job seekers — of which roughly 17 percent were former federal employees — with more than 500 local employers.

“The data clearly shows that our local public school systems are top employers in many regions, and we know that teachers are in demand,” the Virginia Department of Education says in an email to EdSurge, adding that local school districts are working on their own recruitment strategies for federal employees.

The efforts are an attempt to tackle a long-standing issue that has only grown in recent years: maintaining and filling the teacher talent pipeline.

“We very much want people to come in to teaching, we want federal workers who are displaced by the policies of the administration to consider teaching, but definitely that shortage is a real thing with thousands of vacancies in Maryland,” Paul Lemle, president of the Maryland State Education Association, said in an interview with a D.C. Fox News affiliate.

In a separate interview with the same news station, he added that the federal workers could go beyond teaching and help the education sector in a variety of roles, from researchers to policymakers, given their backgrounds.

“That teacher shortage is bigger than just teachers, and in teaching, we always need experts,” he says. “So some of these people are probably data scientists and chemists and people with serious policy chops. So we’re excited about the opportunity to invite people into what we think is a great profession.”

By the Numbers

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, a majority of schools had trouble filling at least one qualified teacher spot in the 2023-2024 school year, with districts seeing six teacher vacancies on average. In 2024, Maryland had roughly 1,900 vacancies, Virginia had roughly 3,650 and Washington, D.C., had 288, according to the Learning Policy Institute.

Megan Boren, project manager at the Southern Regional Education Board, previously told EdSurge there was not just one sole contributing factor causing the teacher shortage, and instead it’s influenced by a cocktail of less-than-ideal working conditions, including stress from lack of planning time and pandemic-related mental health woes. There is also the long-known issue of low teacher pay.

The loss of teachers each year is compounded by many school districts grappling with shrinking budgets, therefore leaving some vacancies untouched.

However, districts in both Maryland and Virginia are deploying state grants to overcome that hiring hurdle by providing alternative pathways into teaching.

Virginia received a $6 million state apprenticeship grant from the U.S. Department of Labor, which will facilitate 50 school divisions partnering with 11 educator preparation programs to prepare roughly 170 teacher apprentices in the coming school year.

And Maryland is providing $1 million in grants to 11 local higher education institutions to create or expand online programs that will allow laid off federal workers to earn teaching licenses, in their “Alternative Certification for Effective Teachers” program.

The state also has Montgomery College’s “Fed to Ed” program that specifically focuses on laid off federal employees undergoing alternative certification to receive a teaching license.

“We’re nowhere near the levels of enrollment in traditional preparation that we were many years ago; that’s something we see across the nation, and we need programs like this if we want to prepare teachers,” Meadows says. “These are not new programs; they’ve been around Maryland for many years, and this is an opportunity for them to shine.”

This post is exclusively published on eduexpertisehub.com

Source link